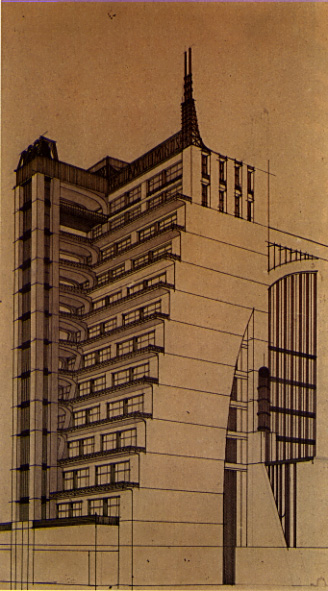

No architecture has existed since 1700. A moronic mixture of the most various stylistic elements used to mask the skeletons of modern houses is called modern architecture. The new beauty of cement and iron are profaned by the superimposition of motley decorative incrustations that cannot be justified either by constructive necessity or by our (modern) taste, and whose origins are in Egyptian, Indian or Byzantine antiquity and in that idiotic flowering of stupidity and impotence that took the name of neoclassicism.

These architectonic prostitutions are welcomed in Italy, and rapacious alien ineptitude is passed off as talented invention and as extremely up-to-date architecture. Young Italian architects (those who borrow originality from clandestine and compulsive devouring of art journals) flaunt their talents in the new quarters of our towns, where a hilarious salad of little ogival columns, seventeenth-century foliation, Gothic pointed arches, Egyptian pilasters, rococo scrolls, fifteenth-century cherubs, swollen caryatids, take the place of style in all seriousness, and presumptuously put on monumental airs. The kaleidoscopic appearance and reappearance of forms, the multiplying of machinery, the daily increasing needs imposed by the speed of communications, by the concentration of population, by hygiene, and by a hundred other phenomena of modern life, never cause these self-styled renovators of architecture a moment's perplexity or hesitation. They persevere obstinately with the rules of Vitruvius, Vignola and Sansovino plus gleanings from any published scrap of information on German architecture that happens to be at hand. Using these, they continue to stamp the image of imbecility on our cities, our cities which should be the immediate and faithful projection of ourselves.

And so this expressive and synthetic art has become in their hands a vacuous stylistic exercise, a jumble of ill-mixed formulae to disguise a run-of-the-mill traditionalist box of bricks and stone as a modern building. As if we who are accumulators and generators of movement, with all our added mechanical limbs, with all the noise and speed of our life, could live in streets built for the needs of men four, five or six centuries ago.

This is the supreme imbecility of modern architecture, perpetuated by the venal complicity of the academies, the internment camps of the intelligentsia, where the young are forced into the onanistic recopying of classical models instead of throwing their minds open in the search for new frontiers and in the solution of the new and pressing problem: the Futurist house and city. The house and the city that are ours both spiritually and materially, in which our tumult can rage without seeming a grotesque anachronism.

The problem posed in Futurist architecture is not one of linear rearrangement. It is not a question of finding new moldings and frames for windows and doors, of replacing columns, pilasters and corbels with caryatids, flies and frogs. Neither has it anything to do with leaving a façade in bare brick, or plastering it, or facing it with stone or in determining formal differences between the new building and the old one. It is a question of tending the healthy growth of the Futurist house, of constructing it with all the resources of technology and science, satisfying magisterially all the demands of our habits and our spirit, trampling down all that is grotesque and antithetical (tradition, style, aesthetics, proportion), determining new forms, new lines, a new harmony of profiles and volumes, an architecture whose reason for existence can be found solely in the unique conditions of modern life, and in its correspondence with the aesthetic values of our sensibilities. This architecture cannot be subjected to any law of historical continuity. It must be new, just as our state of mind is new.

The art of construction has been able to evolve with time, and to pass from one style to another, while maintaining unaltered the general characteristics of architecture, because in the course of history changes of fashion are frequent and are determined by the alternations of religious conviction and political disposition. But profound changes in the state of the environment are extremely rare, changes that unhinge and renew, such as the discovery of natural laws, the perfecting of mechanical means, the rational and scientific use of material. In modern life the process of stylistic development in architecture has been brought to a halt. Architecture now makes a break with tradition. It must perforce make a fresh start.

Calculations based on the resistance of materials, on the use of reinforced concrete and steel, exclude "architecture" in the classical and traditional sense. Modern constructional materials and scientific concepts are absolutely incompatible with the disciplines of historical styles, and are the principal cause of the grotesque appearance of "fashionable" buildings in which attempts are made to employ the lightness, the superb grace of the steel beam, the delicacy of reinforced concrete, in order to obtain the heavy curve of the arch and the bulkiness of marble.

The utter antithesis between the modern world and the old is determined by all those things that formerly did not exist. Our lives have been enriched by elements the possibility of whose existence the ancients did not even suspect. Men have identified material contingencies, and revealed spiritual attitudes, whose repercussions are felt in a thousand ways. Principal among these is the formation of a new ideal of beauty that is still obscure and embryonic, but whose fascination is already felt even by the masses. We have lost our predilection for the monumental, the heavy, the static, and we have enriched our sensibility with a taste for the light, the practical, the ephemeral and the swift. We no longer feel ourselves to be the men of the cathedrals, the palaces and the podiums. We are the men of the great hotels, the railway stations, the immense streets, colossal ports, covered markets, luminous arcades, straight roads and beneficial demolitions.

We must invent and rebuild the Futurist city like an immense and tumultuous shipyard, agile, mobile and dynamic in every detail; and the Futurist house must be like a gigantic machine. The lifts must no longer be hidden away like tapeworms in the niches of stairwells; the stairwells themselves, rendered useless, must be abolished, and the lifts must scale the lengths of the façades like serpents of steel and glass. The house of concrete, glass and steel, stripped of paintings and sculpture, rich only in the innate beauty of its lines and relief, extraordinarily "ugly" in its mechanical simplicity, higher and wider according to need rather than the specifications of municipal laws. It must soar up on the brink of a tumultuous abyss: the street will no longer lie like a doormat at ground level, but will plunge many stories down into the earth, embracing the metropolitan traffic, and will be linked up for necessary interconnections by metal gangways and swift-moving pavements.

The decorative must be abolished. The problem of Futurist architecture must be resolved, not by continuing to pilfer from Chinese, Persian or Japanese photographs or fooling around with the rules of Vitruvius, but through flashes of genius and through scientific and technical expertise. Everything must be revolutionized. Roofs and underground spaces must be used; the importance of the façade must be diminished; issues of taste must be transplanted from the field of fussy moldings, finicky capitals and flimsy doorways to the broader concerns of bold groupings and masses, and large-scale disposition of planes. Let us make an end of monumental, funereal and commemorative architecture. Let us overturn monuments, pavements, arcades and flights of steps; let us sink the streets and squares; let us raise the level of the city.

I COMBAT AND DESPISE:

AND PROCLAIM:

In their bold revolution, the Impressionists made some confused, hesitant attempts at sounds and noises in their pictures. Before them nothing, absolutely nothing!

However, we should point out at once that between the Impressionists’ swarming brush-strokes and our Futurist paintings of sounds, noises and smells there is an enormous difference, like the contrast between a misty winter morning and a sweltering summer afternoon, or to put it better, between the first signs of pregnancy and an adult man in his fully developed strength.

In the Impressionist canvases, sounds and noises are expressed in such a thin, faded way that they might have been perceived by the eardrum of a deaf man. This is not the place for a detailed account of the principles and experiments of the Impressionists. There is no need to enquire minutely into all the reasons why the Impressionists never succeeded in painting sounds, noises and smells. We shall only mention here what they would have had to drop to obtain results:

We Futurists therefore claim that in bringing the elements of sound, noise and smell to painting we are opening fresh paths. We have already taught artists to love our essentially dynamic modern life with its sounds, noises and smells, thereby destroying the stupid passion for values which are solemn, academic, serene, hieratic and mummified: everything purely intellectual, in fact. Imagination without strings, words-in-freedom, the systematic use of onomatopoeia, antigraceful music without rhythmic quadrature, and the art of noises —these were created by the same Futurist sensibility that has given birth to the painting of sounds, noises and smells.

It is indisputably true that (1) silence is static and sounds, noises and smells are dynamic; (2) sounds, noises and smells are nothing but different forms and intensities of vibration; and (3) any succession of sounds, noises and smells impresses on the mind an arabesque of form and color. We must measure this intensity and perceive these arabesques.

The painting of sounds, noises and smells rejects:

The painting of sounds, noises and smells calls for:

These polyphonic and polyrhythmic abstract plastic wholes correspond to a requirement of inner enharmonics that we Futurist painters believe to be indispensable to pictorial sensibility.

These plastic wholes have a mysterious fascination and are more meaningful than those created by our visual and tactile senses, being closer to our pure plastic spirit.

We Futurist painters maintain that sounds noises and smells are incorporated in the expression of lines, volumes and colors just as lines, volumes and colors are incorporated in the architecture of a musical work. Our canvases will therefore express the plastic equivalents of the sounds noises and smells found in theaters, music-halls, cinemas, brothels, railway stations, ports, garages, hospitals, workshops, etc., etc.

From the point of view of form: sounds, noises and smells can be concave, convex triangular, ellipsoidal, oblong, conical, spherical, spiral, etc.

From the point of view of color: sounds, noises and smells can be yellow, green, dark blue, light blue or purple. In railway stations and garages, and throughout the mechanical and sporting world, sounds, noises and smells are predominantly red; in restaurants and cafes they are silver, yellow and purple. While the sounds, noises and smells of animals are yellow and blue, those of a woman are green, blue and purple.

We do not exaggerate in claiming that smell alone is enough to create in our minds arabesques of form and color which can constitute the motive and justify the necessity of a painting. In fact, if we are shut in a dark room (so that our sense of sight no longer functions) with flowers petrol or other strong-smelling things, our plastic spirit gradually eliminates the memory sensations and constructs particular plastic wholes whose quality of weight and movement corresponds perfectly to the smells found in the room. These smells, through an obscure process, have become an environment-force, determining that state of mind which for us Futurist painters constitutes a pure plastic whole.

This bubbling and whirling of forms and lights composed of sounds, noises and smells has been partly rendered by me in my Anarchist’s Funeral and Jolts of a Taxi-cab by Boccioni in States of Mind and Forces of a Street, by Russolo in Revolt and Severini in Pan Pan, paintings which aroused violent controversy at our first Paris Exhibition in 1912. This kind of bubbling over requires a powerful emotion, even delirium, on the part of the artist, who in order to render a vortex must be a vortex of sensation himself, a pictorial force and not a cold logical intellect.

This is the truth! In order to achieve this total painting, which requires the active cooperation of all the senses, a painting which is a plastic state of mind of the universal, you must paint, as drunkards sing and vomit, sounds, noises and smells!

We have recently had the pleasure of fighting in the streets with the most fervent adversaries of the war, and shouting in their faces our firm beliefs:

For us today, Italy has the shape and power of a fine Dreadnought battleship with its squadron of torpedo-boat islands. Proud to feel that the marital fervor throughout the Nation is equal to ours, we urge the Italian government, Futurist at last, to magnify all the national ambitions, disdaining the stupid accusations of piracy, and proclaim the birth of Panitalianism.

Futurist poets, painters, sculptors, and musicians of Italy! As long as the war lasts let us set aside our verse, our brushes, scapels, and orchestras! The red holidays of genius have begun! There is nothing for us to admire today but the dreadful symphonies of the shrapnels and the mad sculptures that our inspired artillery molds among the masses of the enemy.

We Futurists, Balla and Depero, seek to realize this total fusion in order to reconstruct the universe making it more joyful, in other words by a complete re-creation.

We will give skeleton and flesh to the invisible, the impalpable, the imponderable and the imperceptible. We will find abstract equivalents for every form and element in the universe, and then we will combine them according to the caprice of our inspiration, creating plastic complexes which we will set in motion.

Balla initially studied the speed of automobiles, thus discovering the laws and essential line-forces of speed. After more than twenty exploratory paintings, he understood that the flat plane of the canvas prevented him from reproducing the dynamic volume of speed in depth. Balla felt the need to construct, with strands of wire, cardboard sheets, fabrics, tissue paper, etc., the first dynamic plastic complex.

Necessary means: Colored strands of wire, cotton, wool, silk, of every thickness. Colored glass, tissue paper, celluloid, wire netting, every sort of transparent and bright material. Fabrics, mirrors, sheets of metal, colored tin-foil, every sort of gaudy material. Mechanical and electrical devices; musical and noise-making elements, chemically luminous liquids of variable colors; springs, levers, tubes, etc. With these means we will construct:

Rotations:

Decompositions:

Miracle Magic:

Using complex, constructive, noise-producing abstraction, in short, the Futurist style. Every action developed in space, every emotion felt, will represent for us a possible discovery.

Examples: Watching an aeroplane swiftly climbing while a band played in the square, we had the idea of plastic-motor-noise music in space and the launching of aerial concerts above the city. The need to keep changing our environment, together with sport, led us to the idea of transformable clothes (mechanical trimmings, surprises, tricks, disappearance of individuals). The simultaneity of speed and noises inspired the rotoplastic noise fountain. Tearing up a book and throwing it down into a courtyard resulted in phono-moto-plastic advertisement and pyrotechnic-plastic-abstract contests. A spring garden blown by the wind led to the concept of the Magical transformable motor-noise flower. — Clouds flying in a storm suggested buildings in noise-ist transformable style.

In games and toys, as in all traditionalist manifestations, there is nothing but grotesque imitation, timidity (little trains, prams, puppets), immobile objects, stupid caricatures of domestic objects, antigymnastic and monotonous, which can only cretinize and depress a child.

With plastic complexes we will construct toys which will accustom the child:

The Futurist toy will be very useful to adults too, keeping them young, agile, jubilant, spontaneous, ready for anything, untiring, instinctive and intuitive.

By developing the first synthesis of the speed of an automobile, Balla created the first plastic ensemble. This revealed an abstract landscape composed of cones, pyramids, polyhedrons, and the spiral of mountains, rivers, lights and shadows. Evidently a profound analogy exists between the essential line-forces of speed and the essential line-forces of a landscape. We have reached the deepest essence of the universe and have mastered the elements. We shall thus be able to construct.

Fusion of art + science. Chemistry, physics, continuous and unexpected pyrotechnics all incorporated into a new creature, a creature that will speak, shout and dance automatically. We Futurists, Balla and Depero, will construct millions of metallic animals for the greatest war (conflagration of all the creative energies of Europe, Asia, Africa and America, which will undoubtedly follow the current marvelous little human conflagration).

The inventions contained in this manifesto are absolute creations, generated entirely by Italian Futurism. No artist in France, Russia, England or Germany anticipated us by inventing anything similar or analogous. Only the Italian genius, which is the most constructive and architectural, could invent the abstract plastic ensemble. With this Futurism has determined its style, which will inevitably dominate the sensibility of many centuries to come.

In Rome, in the Costanzi Theatre, packed to capacity, while I was listening to the orchestral performance of your overwhelming Futurist music, with my Futurist friends, Marinetti, Boccioni, Carrà, Balla, Soffici, Papini and Cavacchioli, a new art came into my mind which only you can create, the Art of Noises, the logical consequence of your marvelous innovations.

Ancient life was all silence. In the nineteenth century, with the invention of the machine, Noise was born. Today, Noise triumphs and reigns supreme over the sensibility of men. For many centuries life went by in silence, or at most in muted tones. The strongest noises which interrupted this silence were not intense or prolonged or varied. If we overlook such exceptional movements as earthquakes, hurricanes, storms, avalanches and waterfalls, nature is silent.

Amidst this dearth of noises, the first sounds that man drew from a pieced reed or streched string were regarded with amazement as new and marvelous things. Primitive races attributed sound to the gods; it was considered sacred and reserved for priests, who used it to enrich the mystery of their rites.

And so was born the concept of sound as a thing in itself, distinct and independent of life, and the result was music, a fantastic world superimposed on the real one, an inviolatable and sacred world. It is easy to understand how such a concept of music resulted inevitable in the hindering of its progress by comparison with the other arts. The Greeks themselves, with their musical theories calculated mathematically by Pythagoras and according to which only a few consonant intervals could be used, limited the field of music considerably, rendering harmony, of which they were unaware, impossible. ![[Photo of 'Noise Intoners']](http://www.unknown.nu/futurism/images/intonarumori2.jpg)

The Middle Ages, with the development and modification of the Greek tetrachordal system, with the Gregorian chant and popular songs, enriched the art of music, but continued to consider sound in its development in time, a restricted notion, but one which lasted many centuries, and which still can be found in the Flemish contrapuntalists’ most complicated polyphonies.

The chord did not exist, the development of the various parts was not subornated to the chord that these parts put together could produce; the conception of the parts was horizontal not vertical. The desire, search, and taste for a simultaneous union of different sounds, that is for the chord (complex sound), were gradually made manifest, passing from the consonant perfect chord with a few passing dissonances, to the complicated and persistent dissonances that characterize contemporary music.

At first the art of music sought purity, limpidity and sweetness of sound. Then different sounds were amalgamated, care being taken, however, to caress the ear with gentle harmonies. Today music, as it becomes continually more complicated, strives to amalgamate the most dissonant, strange and harsh sounds. In this way we come ever closer to noise-sound.

This musical evolution is paralleled by the multipication of machines, which collaborate with man on every front. Not only in the roaring atmosphere of major cities, but in the country too, which until yesterday was totally silent, the machine today has created such a variety and rivalry of noises that pure sound, in its exiguity and monotony, no longer arouses any feeling.

To excite and exalt our sensibilities, music developed towards the most complex polyphony and the maximum variety, seeking the most complicated successions of dissonant chords and vaguely preparing the creation of musical noise. This evolution towards “noise sound” was not possible before now. The ear of an eighteenth-century man could never have endured the discordant intensity of certain chords produced by our orchestras (whose members have trebled in number since then). To our ears, on the other hand, they sound pleasant, since our hearing has already been educated by modern life, so teeming with variegated noises. But our ears are not satisfied merely with this, and demand an abundance of acoustic emotions.

On the other hand, musical sound is too limited in its qualitative variety of tones. The most complex orchestras boil down to four or five types of instrument, varying in timber: instruments played by bow or plucking, by blowing into metal or wood, and by percussion. And so modern music goes round in this small circle, struggling in vain to create new ranges of tones.

This limited circle of pure sounds must be broken, and the infinite variety of “noise-sound” conquered.

Besides, everyone will acknowledge that all musical sound carries with it a development of sensations that are already familiar and exhausted, and which predispose the listener to boredom in spite of the efforts of all the innovatory musicians. We Futurists have deeply loved and enjoyed the harmonies of the great masters. For many years Beethoven and Wagner shook our nerves and hearts. Now we are satiated and we find far more enjoyment in the combination of the noises of trams, backfiring motors, carriages and bawling crowds than in rehearsing, for example, the “Eroica” or the “Pastoral”. ![[Painting by Luigi Russolo]](http://www.unknown.nu/futurism/images/russolo.jpg)

We cannot see that enormous apparatus of force that the modern orchestra represents without feeling the most profound and total disillusion at the paltry acoustic results. Do you know of any sight more ridiculous than that of twenty men furiously bent on the redoubling the mewing of a violin? All this will naturally make the music-lovers scream, and will perhaps enliven the sleepy atmosphere of concert halls. Let us now, as Futurists, enter one of these hospitals for anaemic sounds. There: the first bar brings the boredom of familiarity to your ear and anticipates the boredom of the bar to follow. Let us relish, from bar to bar, two or three varieties of genuine boredom, waiting all the while for the extraordinary sensation that never comes.

Meanwhile a repugnant mixture is concocted from monotonous sensations and the idiotic religious emotion of listeners buddhistically drunk with repeating for the nth time their more or less snobbish or second-hand ecstasy.

Away! Let us break out since we cannot much longer restrain our desire to create finally a new musical reality, with a generous distribution of resonant slaps in the face, discarding violins, pianos, double-basses and plainitive organs. Let us break out!

It’s no good objecting that noises are exclusively loud and disagreeable to the ear.

It seems pointless to enumerate all the graceful and delicate noises that afford pleasant sensations.

To convince ourselves of the amazing variety of noises, it is enough to think of the rumble of thunder, the whistle of the wind, the roar of a waterfall, the gurgling of a brook, the rustling of leaves, the clatter of a trotting horse as it draws into the distance, the lurching jolts of a cart on pavings, and of the generous, solemn, white breathing of a nocturnal city; of all the noises made by wild and domestic animals, and of all those that can be made by the mouth of man without resorting to speaking or singing.

Let us cross a great modern capital with our ears more alert than our eyes, and we will get enjoyment from distinguishing the eddying of water, air and gas in metal pipes, the grumbling of noises that breathe and pulse with indisputable animality, the palpitation of valves, the coming and going of pistons, the howl of mechanical saws, the jolting of a tram on its rails, the cracking of whips, the flapping of curtains and flags. We enjoy creating mental orchestrations of the crashing down of metal shop blinds, slamming doors, the hubbub and shuffling of crowds, the variety of din, from stations, railways, iron foundries, spinning wheels, printing works, electric power stations and underground railways.

Nor should the newest noises of modern war be forgotten. Recently, the poet Marinetti, in a letter from the trenches of Adrianopolis, described to me with marvelous free words the orchestra of a great battle:

“every 5 seconds siege cannons gutting space with a chord ZANG-TUMB-TUUMB mutiny of 500 echos smashing scattering it to infinity. In the center of this hateful ZANG-TUMB-TUUMB area 50square kilometers leaping bursts lacerations fists rapid fire batteries. Violence ferocity regularity this deep bass scanning the strange shrill frantic crowds of the battle Fury breathless ears eyes nostrils open! load! fire! what a joy to hear to smell completely taratatata of the machine guns screaming a breathless under the stings slaps traak-traak whips pic-pac-pum-tumb weirdness leaps 200 meters range Far far in back of the orchestra pools muddying huffing goaded oxen wagons pluff-plaff horse action flic flac zing zing shaaack laughing whinnies the tiiinkling jiiingling tramping 3 Bulgarian battalions marching croooc-craaac [slowly] Shumi Maritza or Karvavena ZANG-TUMB-TUUUMB toc-toc-toc-toc [fast] crooc-craac [slowly] crys of officers slamming about like brass plates pan here paak there BUUUM ching chaak [very fast] cha-cha-cha-cha-chaak down there up around high up look out your head beautiful! Flashing flashing flashing flashing flashing flashing footlights of the forts down there behind that smoke Shukri Pasha communicates by phone with 27 forts in Turkish in German Allo! Ibrahim! Rudolf! allo! allo! actors parts echos of prompters scenery of smoke forests applause odor of hay mud dung I no longer feel my frozen feet odor of gunsmoke odor of rot Tympani flutes clarinets everywhere low high birds chirping blessed shadows cheep-cheep-cheep green breezes flocks don-dan-don-din-baaah Orchestra madmen pommel the performers they terribly beaten playing Great din not erasing clearing up cutting off slighter noises very small scraps of echos in the theater area 300 square kilometers Rivers Maritza Tungia stretched out Rodolpi Mountains rearing heights loges boxes 2000 shrapnels waving arms exploding very white handkerchiefs full of gold srrrr-TUMB-TUMB 2000 raised grenades tearing out bursts of very black hair ZANG-srrrr-TUMB-ZANG-TUMB-TUUMB the orchestra of the noises of war swelling under a held note of silence in the high sky round golden balloon that observes the firing...”

To attune noises does not mean to detract from all their irregular movements and vibrations in time and intensity, but rather to give gradation and tone to the most strongly predominant of these vibrations.

Noise in fact can be differentiated from sound only in so far as the vibrations which produce it are confused and irregular, both in time and intensity.

Every noise has a tone, and sometimes also a harmony that predominates over the body of its irregular vibrations.

Now, it is from this dominating characteristic tone that a practical possibility can be derived for attuning it, that is to give a certain noise not merely one tone, but a variety of tones, without losing its characteristic tone, by which I mean the one which distinguishes it. In this way any noise obtained by a rotating movement can offer an entire ascending or descending chromatic scale, if the speed of the movement is increased or decreased.

Every manifestation of our life is accompanied by noise. The noise, therefore, is familiar to our ear, and has the power to conjure up life itself. Sound, alien to our life, always musical and a thing unto itself, an occasional but unnecessary element, has become to our ears what an overfamiliar face is to our eyes. Noise, however, reaching us in a confused and irregular way from the irregular confusion of our life, never entirely reveals itself to us, and keeps innumerable surprises in reserve. We are therefore certain that by selecting, coordinating and dominating all noises we will enrich men with a new and unexpected sensual pleasure.

Although it is characteristic of noise to recall us brutally to real life, the art of noise must not limit itself to imitative reproduction. It will achieve its most emotive power in the acoustic enjoyment, in its own right, that the artist’s inspiration will extract from combined noises.

Here are the 6 families of noises of the Futurist orchestra which we will soon set in motion mechanically:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rumbles Roars Explosions Crashes Splashes Booms | Whistles Hisses Snorts | Whispers Murmurs Mumbles Grumbles Gurgles | Screeches Creaks Rumbles Buzzes Crackles Scrapes | Noises obtained by percussion on metal, wood, skin, stone, tarracotta, etc. | Voices of animals and men: Shouts Screams Groans Shrieks Howls Laughs Weezes Sobs |

Dear Pratella, I submit these statements to your Futurist genius, inviting your discussion. I am not a musician, I have therefore no acoustical predilictions, nor any works to defend. I am a Futurist painter using a much loved art to project my determination to renew everything. And so, bolder than a professional musician could be, unconcerned by my apparent incompetence and convinced that all rights and possibilities open up to daring, I have been able to initiate the great renewal of music by means of the Art of Noises.

My Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature, with which I invented essential and synthetic lyricism, imagination without strings, and words-in-freedom, deals exclusively with poetic inspiration.

Philosophy, the exact sciences, politics, journalism, education, business, however much they may seek synthetic forms of expression, will still need to use syntax and punctuation. I am obliged, for that matter, to use them myself in order to make myself clear to you.

Futurism is grounded in the complete renewal of human sensibility brought about by the great discoveries of science. Those people who today make use of the telegraph, the telephone, the phonograph, the train, the bicycle, the motorcycle, the automobile, the ocean liner, the dirigible, the aeroplane, the cinema, the great newspaper (synthesis of a day in the world’s life) do not realize that these various means of communication, transportation and information have a decisive influence on their psyches.

An ordinary man can in a day’s time travel by train from a little dead town of empty squares, where the sun, the dust, and the wind amuse themselves in silence, to a great capital city bristling with lights, gestures, and street cries. By reading a newspaper the inhabitant of a mountain village can tremble each day with anxiety, following insurrection in China, the London and New York suffragettes, Doctor Carrel, and the heroic dog-sleds of the polar explorers. The timid, sedentary inhabitant of any provincial town can indulge in the intoxication of danger by going to the movies and watching a great hunt in the Congo. He can admire Japanese athletes, Negro boxers, tireless American eccentrics, the most elegant Parisian women, by paying a franc to go to the variety theater. Then, back in his bourgeois bed, he can enjoy the distant, expensive voice of a Caruso or a Burzio.

Having become commonplace, these opportunities arouse no curiosity in superficial minds who are as incapable of grasping any novel facts as the Arabs who looked with indifference at the first aeroplanes in the sky of Tripoli. For the keen observer, however, these facts are important modifiers of our sensibility because they have caused the following significant phenomena:

So these are some elements of the new Futurist sensibility that has generated our pictorial dynamism, our antigraceful music in its free, irregular rhythms, our noise-art and our words-in-freedom.

Words-in-freedom

Casting aside every stupid formula and all the confused verbalisms of the professors, I now declare that lyricism is the exquisite faculty of intoxicating oneself with life, of filling life with the inebriation of oneself. The faculty of changing into wine the muddy water of the life that swirls and engulfs us. The ability to color the world with the unique colors of our changeable selves.

Now suppose that a friend of yours gifted with this faculty finds himself in a zone of intense life (revolution, war, shipwreck, earthquake, and so on) and starts right away to tell you his impressions. Do you know what this lyric, excited friend of yours will instinctively do?

He will begin by brutally destroying the syntax of his speech. He wastes no time in building sentences. Punctuation and the right adjectives will mean nothing to him. He will despise subtleties and nuances of language. Breathlessly he will assault your nerves with visual, auditory, olfactory sensations, just as they come to him. The rush of steam-emotion will burst the sentence’s steampipe, the valves of punctuation, and the adjectival clamp. Fistfuls of essential words in no conventional order. Sole preoccupation of the narrator, to render every vibration of his being.

If the mind of this gifted lyrical narrator is also populated by general ideas, he will involuntarily bind up his sensations with the entire universe that he intuitively knows. And in order to render the true worth and dimensions of his lived life, he will cast immense nets of analogy across the world. In this way he will reveal the analogical foundation of life, telegraphically, with the same economical speed that the telegraph imposes on reporters and war correspondents in their swift reportings. This urgent laconism answers not only to the laws of speed that govern us but also to the rapport of centuries between poet and audience. Between poet and audience, in fact, the same rapport exists as between two old friends. They can make themselves understood with half a word, a gesture, a glance. So the poet’s imagination must weave together distant things with no connecting strings, by means of essential free words.

Death of free verse

Free verse once had countless reasons for existing but now is destined to be replaced by words-in-freedom.

The evolution of poetry and human sensibility has shown us the two incurable defects of free verse.

When I speak of destroying the canals of syntax, I am neither categorical nor systematic. Traces of conventional syntax and even of true logical sentences will be found here and there in the words-in-freedom of my unchained lyricism. This inequality in conciseness and freedom is natural and inevitable. Since poetry is in truth only a superior, more concentrated and intense life than what we live from day to day, like the latter it is composed of hyper-alive elements and moribund elements.

We ought not, therefore, to be too much preoccupied with these elements. But we should at all costs avoid rhetoric and banalities telegraphically expressed.

The imagination without strings

By the imagination without strings I mean the absolute freedom of images or analogies, expressed with unhampered words and with no connecting strings of syntax and with no punctuation.

Up to now writers have been restricted to immediate analogies. For instance, they have compared an animal with a man or with another animal, which is almost the same as a kind of photography. (They have compared, for example, a fox terrier to a very small thoroughbred. Others, more advanced, might compare the same trembling fox terrier to a little Morse Code machine. I, on the other hand, compare it with gurgling water. In this there is an ever vaster gradation of analogies, there are ever deeper and more solid affinities, however remote.)Analogy is nothing more than the deep love that assembles distant, seemingly diverse and hostile things. An orchestral style, at once polychromatic, polyphonic, and polymorphous, can embrace the life of matter only by means of the most extensive analogies.

When, in my Battle of Tripoli, I compared a trench bristling with bayonets to an orchestra, a machine gun to a femme fatale, I intuitively introduced a large part of the universe into a short episode of African battle.

Images are not flowers to be chosen and picked with parsimony, as Voltaire said. They are the very lifeblood of poetry. Poetry should be an uninterrupted sequence of new images, Or it is mere anemia and greensickness.

The broader their affinities, the longer will images keep their power to amaze.

The imagination without strings, and words-in-freedom, will bring us to the essence of material. As we discover new analogies between distant and apparently contrary things, we will endow them with an ever more intimate value. Instead of humanizing animals, vegetables, and minerals (an outmoded system) we will be able to animalize, vegetize, mineralize, electrify, or liquefy our style, making it live the life of material. For example, to represent the life of a blade of grass, I say, “Tomorrow I’ll be greener.”

With words-in-freedom we will have: Condensed metaphors. Telegraphic images. Maximum vibrations. Nodes of thought. Closed or open fans of movement. Compressed analogies. Color Balances. Dimensions, weights, measures, and the speed of sensations. The plunge of the essential word into the water of sensibility, minus the concentric circles that the word produces. Restful moments of intuition. Movements in two, three, four, five different rhythms. The analytic, exploratory poles that sustain the bundle of intuitive strings.

Death of the literary I

Molecular life and material

My technical manifesto opposed the obsessive I that up to now the poets have described, sung, analyzed, and vomited up. To rid ourselves of this obsessive I, we must abandon the habit of humanizing nature by attributing human passions and preoccupations to animals, plants, water, stone, and clouds. Instead we should express the infinite smallness that surrounds us, the imperceptible, the invisible, the agitation of atoms, the Brownian movements, all the passionate hypotheses and all the domains explored by the high-powered microscope. To explain: I want to introduce the infinite molecular life into poetry not as a scientific document but as an intuitive element. It should mix, in the work of art, with the infinitely great spectacles and dramas, because this fusion constitutes the integral synthesis of life.

To give some aid to the intuition of my ideal reader I use italics for all words-in-freedom that express the infinitely small and the molecular life.

Semaphoric adjective

Lighthouse-adjective or atmosphere-adjective

Everywhere we tend to suppress the qualifying adjective because it presupposes an arrest in intuition, too minute a definition of the noun. None of this is categorical. I speak of a tendency. We must make use of the adjective as little as possible and in a manner completely different from its use hitherto. One should treat adjectives like railway signals of style, employ them to mark the tempo, the retards and pauses along the way. So, too, with analogies. As many as twenty of these semaphoric adjectives might accumulate in this way.

What I call a semaphoric adjective, lighthouse-adjective, or atmosphere-adjective is the adjective apart from nouns, isolated in parentheses. This makes it a kind of absolute noun, broader and more powerful than the noun proper.

The semaphoric adjective or lighthouse-adjective, suspended on high in its glassed-in parenthetical cage, throws its far-reaching, probing light on everything around it.

The profile of this adjective crumbles, spreads abroad, illuminating, impregnating, and enveloping a whole zone of words-in-freedom. If, for instance, in an agglomerate of words-in-freedom describing a sea voyage I place the following semaphoric adjectives between parentheses: (calm, blue, methodical, habitual) not only the sea is calm, blue, methodical, habitual, but the ship, its machinery, the passengers. What I do and my very spirit are calm, blue, methodical, habitual.

The infinitive verb

Here, too, my pronouncements are not categorical. I maintain, however, that in a violent and dynamic lyricism the infinitive verb might well be indispensable. Round as a wheel, like a wheel adaptable to every car in the train of analogies, it constitutes the very speed of the style.

The infinitive in itself denies the existence of the sentence and prevents the style from slowing and stopping at a definite point. While the infinitive is round and as mobile as a wheel, the other moods and tenses of the verb are either triangular, square, or oval.

Onomatopoeia and mathematical symbols

When I said that we must spit on the Altar of Art, I incited the Futurists to liberate lyricism from the solemn atmosphere of compunction and incense that one normally calls by the name of Art with a capital A. Art with a capital A constitutes the clericalism of the creative spirit. I used this approach to incite the Futurists to destroy and mock the garlands, the palms, the aureoles, the exquisite frames, the mantles and stoles, the whole historical wardrobe and the romantic bric-a-brac that comprise a large part of all poetry up to now. I proposed instead a swift, brutal, and immediate lyricism, a lyricism that must seem antipoetic to all our predecessors, a telegraphic lyricism with no taste of the book about it but, rather, as much as possible of the taste of life. Beyond that the bold introduction of onomatopoetic harmonies to render all the sounds and noises of modern life, even the most cacophonic.

Onomatopoeia that vivifies lyricism with crude and brutal elements of reality was used in poetry (from Aristophanes to Pascoli) more or less timidly. We Futurists initiate the constant, audacious use of onomatopoeia. This should not be systematic. For instance, my Adrianople Siege-Orchestra and my Battle Weight + Smell required many onomatopoetic harmonies. Always with the aim of giving the greatest number of vibrations and a deeper synthesis of life, we abolish all stylistic bonds, all the bright buckles with which the traditional poets link images together in their prosody. Instead we employ the very brief or anonymous mathematical and musical symbols and we put between parentheses indications such as (fast) (faster) (slower) (two-beat time) to control the speed of the style. These parentheses can even cut into a word or an onomatopoetic harmony. ![[Words-in-Freedom, by F.T. Marinetti]](http://www.unknown.nu/futurism/images/words2.jpg)

Typographical revolution

I initiate a typographical revolution aimed at the bestial, nauseating idea of the book of passéist and D’Annunzian verse, on seventeenth-century handmade paper bordered with helmets, Minervas, Apollos, elaborate red initials, vegetables, mythological missal ribbons, epigraphs, and roman numerals. The book must be the Futurist expression of our Futurist thought. Not only that. My revolution is aimed at the so-called typographical harmony of the page, which is contrary to the flux and reflux, the leaps and bursts of style that run through the page. On the same page, therefore, we will use three or four colors of ink, or even twenty different typefaces if necessary. For example: italics for a series of similar or swift sensations, boldface for the violent onomatopoeias, and so on. With this typographical revolution and this multicolored variety in the letters I mean to redouble the expressive force of words.

I oppose the decorative, precious aesthetic of Mallarmé and his search for the rare word, the one indispensable, elegant, suggestive, exquisite adjective. I do not want to suggest an idea or a sensation with passéist airs and graces. Instead I want to grasp them brutally and hurl them in the reader’s face.

Moreover, I combat Mallarmé’s static ideal with this typographical revolution that allows me to impress on the words (already free, dynamic, and torpedo-like) every velocity of the stars, the clouds, aeroplanes, trains, waves, explosives, globules of seafoam, molecules, and atoms.

Thus I realize the fourth principle of my First Futurist Manifesto: “We affirm that the world’s beauty is enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed.”

Multilinear Lyricism

In addition, I have conceived multilinear lyricism, with which I succeed in reaching that lyric simultaneity that obsessed the Futurist painters as well: multilinear lyricism by means of which I am sure to achieve the most complex lyric simultaneities.

On several parallel lines, the poet will throw out several chains of color, sound, smell, noise, weight, thickness, analogy. One of these lines might, for instance, be olfactory, another musical, another pictorial.

Let us suppose that the chain of pictorial sensations and analogies dominates the others. In this case it will be printed in a heavier typeface than the second and third lines (one of them containing, for example, the chain of musical sensations and analogies, the other the chain of olfactory sensations and analogies).

Given a page that contains many bundles of sensations and analogies, each of which is composed of three or four lines, the chain of pictorial sensations and analogies (printed in boldface) will form the first line of the first bundle and will continue (always in the same type) on the first line of all the other bundles.

The chain of musical sensations and analogies, less important than the chain of pictorial sensations and analogies (first line) but more important than that of the olfactory sensations and analogies (third line), will be printed in smaller type than that of the first line and larger than that of the third.

Free expressive orthography

The historical necessity of free expressive orthography is demonstrated by the successive revolutions that have continuously freed the lyric powers of the human race from shackles and rules.